Beyond the Assembly Line: Why Bernie Sanders’ AI Proposals Revive a Century of Economic Labour Reforms

From Roosevelt’s New Deal to the robot tax — America’s long struggle to make technology serve democracy.

Alogopoly invites you to step back from the daily noise and examine the machinery beneath it: how AI is financed, scaled, and governed, and what that means for democracy, labour, and the future balance between code and capital.

Here, I address how Senator Bernie Sanders’ AI proposals fit into a broader historical arc of U.S. reforms—from the New Deal to the digital age—revealing how each era’s response to the “machine question” reshaped the balance between technology, labour, and democracy.

Outline:

I. The Machine Question Returns

II. The 1930s: The Politics of Time and the Origins of the 40-Hour Week

III. The 1940s–1970s: From Industrial Democracy to Codetermination

IV. The 1980s–1990s: Ownership Without Power

V. The 2000s–2020s: The Automation New Deal That Never Came

VI. The Historical Throughline

VII. The Political Economy of the Future

I. The Machine Question Returns

In the digital age, Amazon has become the emblem of a new industrial order — one where automation, not labour, defines the frontier of productivity. As reported by The New York Times (October 2025), the company’s internal plans outline a transition toward warehouses that operate with minimal human presence, automating up to three-quarters of its logistics operations and displacing hundreds of thousands of jobs by the early 2030s. The strategy promises efficiency and profit — saving roughly thirty cents per item — but it also signals a turning point: one of America’s largest employers could soon become a net job destroyer. Daron Acemoglu, professor of economics at MIT and a leading scholar of technology’s impact on labour, warns that once Amazon perfects profitable automation at scale, “it will spread to others too.”

The United States has faced the machine question before.

In the 1930s, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal responded to the mass unemployment of the Great Depression by redistributing not only money but time — forging a social compact that linked productivity to public purpose. By the 1950s, America had institutionalised the 40-hour work week, progressive taxation, and social insurance. Yet each technological revolution — electrification, mechanisation, automation — has rekindled the same anxiety: will machines work for us, or will we work for them?

As historian David F. Noble observed in Forces of Production (1986), every industrial transition has been “a battle over control disguised as a struggle for efficiency.” Noble offered a penetrating critique of how automation in the United States was shaped less by technical necessity than by managerial ideology and political control.

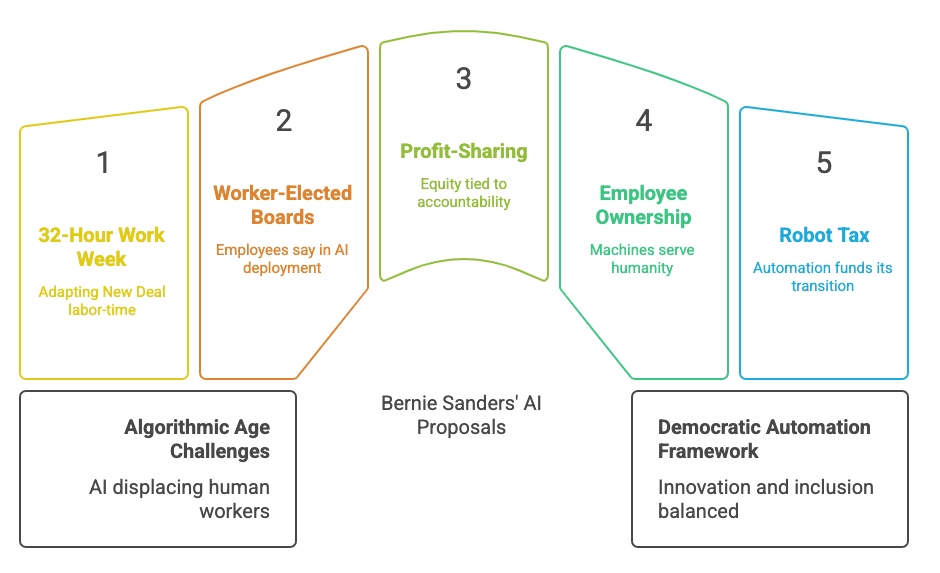

Senator Bernie Sanders’ recent address on artificial intelligence and robotics reopens that century-old debate. His five proposals — shorter work weeks, worker representation on boards, profit-sharing, employee ownership, and a robot tax — may sound radical in today’s context but are deeply rooted in America’s long reform tradition.

The question is not new; only the machinery is. Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (2019) reminds us that data and algorithms have simply replaced assembly lines as the infrastructure of power. The OECD’s Employment Outlook (2023) confirms this continuity: the productivity gains from digital technologies increasingly accrue to capital, not labor.

Senator Sanders’ intervention matters precisely because it insists that this imbalance is a political choice, not a technological destiny.

II. The 1930s: The Politics of Time and the Origins of the 40-Hour Week

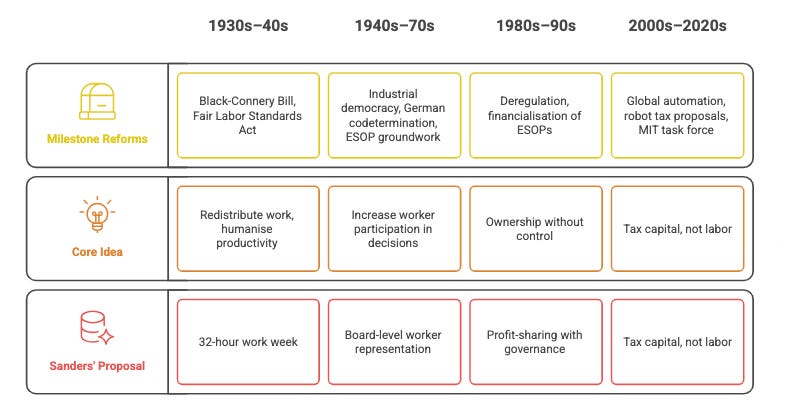

The 32-hour work week, one of Sanders’ flagship ideas, has deeper roots than most realise. During the Great Depression, the Black-Connery Bill of 1933 proposed a 30-hour week to combat unemployment. The Roosevelt administration eventually compromised with the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, setting a 40-hour limit and establishing overtime pay — a deal that spread work more evenly while boosting wages.

As historian Jonathan D. Cutler details in Labor’s Time (2001), these shorter-hour campaigns were not utopian experiments but pragmatic responses to technological displacement in the machine age. Robert C. Allen’s Global Economic History (2011) frames them as early efforts to share productivity gains between capital and workers — the very challenge AI now revives.

In today’s context, the International Labour Organization (2022) argues that reducing working hours is again emerging as an essential policy lever to balance technological productivity with social stability. An earlier Guardian analysis (Nov. 2023) noted that the new 32-hour workweek bills circulating in Congress have direct historical lineage to 1930s labour reform — not as a retreat from productivity, but as its moral recalibration.

Sanders’ proposal thus echoes the logic of the New Deal: redistribute work and time to sustain dignity in the face of machine-driven abundance.

III. The 1940s–1970s: From Industrial Democracy to Codetermination

Senator Sanders’s second and third proposals — worker-elected directors and corporate profit-sharing — recall the “industrial democracy” envisioned during World War II. Labour leaders like Sidney Hillman and Walter Reuther argued that workers should have a voice in how productivity gains were allocated, a vision documented in Nelson Lichtenstein’s Labor’s War at Home (2008).

After 1945, while the United States never institutionalised Mitbestimmung (codetermination) as West Germany did, it briefly experimented with works councils and joint productivity committees. In Germany, these ideas matured into a stable system of shared governance. According to the report by Lionel Fulton (2020), employee representation on boards helped sustain industrial peace and long-term investment far better than the shareholder capitalism model that later dominated the U.S. Lenore Palladino (2019) similarly concludes that codetermination correlates with lower wage inequality and higher firm innovation, but to effectively reduce wage inequality and raise innovation, board representation must be combined with broader stakeholder governance reforms, including redefining fiduciary duties and expanding worker access to information and decision-making.

Recent evidence reinforces these historical lessons. The Aspen Institute (2021) finds that board-level employee representation is not merely symbolic: firms with structured worker participation exhibit higher labour productivity, lower outsourcing rates, and stronger long-term capital investment, suggesting that inclusion strengthens—not hinders—competitive performance. Likewise, Fitzroy and Nolan (2020) demonstrate through cross-country modelling that profit-sharing and codetermination systematically reduce wage inequality and increase worker satisfaction when paired with institutional supports such as collective bargaining and information access. Both studies converge on a central principle: economic democracy is most effective when embedded in corporate governance itself—when employees are not passive shareholders but active stewards of the enterprise’s direction and purpose.

These echoes are unmistakable. Senator Sanders’ 45% worker-representation proposal is less a novelty than an inheritance — one that recovers the spirit of shared prosperity forged in the mid-20th century and lost to financialisation.

IV. The 1980s–1990s: Ownership Without Power

By the 1970s, as stagflation and global competition eroded corporate margins, the focus shifted from participation to ownership. Senator Russell Long’s 1974 Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) legislation promoted the idea that workers could become shareholders — aligning incentives between labor and capital.

Initially, this seemed like a democratic innovation. By the 1980s, however, the ESOP movement had been captured by Wall Street logic. Employees gained shares but not control; ownership was financialised, not democratised. As Joseph Blasi, Douglas Kruse, and Richard Freeman demonstrate in The Citizen’s Share (2014), most ESOPs provided “ownership without power” — workers held equity, yet executives retained all strategic authority. Cooper et al. (2025) find ESOPs increase employee voice only when workers have decision influence—precisely the “symbolic vs. real” distinction.

Sanders’ model — combining profit-sharing with board representation — closes this historical loophole. It seeks not just to share wealth but to distribute governance.

V. The 2000s–2020s: The Automation New Deal That Never Came

After the dot-com crash, economists began warning of a growing disconnect between productivity and employment. The MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future (2020) concluded that the U.S. lacked any coherent strategy for managing automation’s social fallout. Among its major conclusions:

The mismatch between rapidly advancing technologies and outdated labour-market institutions risks deepening income and opportunity gaps;

Technologies must be paired with innovations in education, training, job quality, social insurance to ensure workers benefit;

Rather than fearing wholesale job loss, policy should emphasise job quality, skills investment, and shaping technology so that it augments rather than replaces human work

Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee’s The Second Machine Age (2014) popularised the paradox: technology expands output while eroding labour’s share of income. They describe this as the “great decoupling,” where productivity and median wages diverge, signalling that economic growth no longer guarantees shared prosperity. The authors warn that without institutional reforms, digital innovation will amplify winner-take-all dynamics, concentrating wealth in a few firms while hollowing out middle-class employment. Yet they also argue that this trajectory is not inevitable — with the right policies in education, labour adaptation, and innovation governance, technology can still serve as a force for inclusive progress rather than polarisation.

Despite mounting evidence, the U.S. never enacted a modern “New Deal” for automation. Similarly, in Europe, tax policy has favoured capital expenditure over employment. Training programs remained fragmented and underfunded. The OECD’s digital taxation framework underscores that the persistence of tax structures rooted in the industrial age distorts incentives toward capital-deepening automation while under-taxing intangible, data-driven value creation (Homa, 2023). Corporate tax codes still reward firms for investing in machines that replace labour through accelerated depreciation, yet fail to capture the vast rents generated by algorithms, data, and digital platforms. This imbalance effectively subsidises displacement while depriving governments of the fiscal capacity to finance retraining and social adaptation. As the OECD note, modernising tax regimes to include automation and digital value would not stifle innovation—it would realign it with social purpose, ensuring that progress funds inclusion rather than inequality.

Forbes (February 2025) and The Guardian (June 2024) report that governments are once again debating automation and AI taxes in response to generative AI’s disruption of white-collar labour, with the IMF urging fiscal reforms to capture automation rents and support displaced workers. Sanders’ proposed robot tax fits squarely into that lineage — a fiscal counterpart to the ‘Fair Labor Standards Act’, designed to treat algorithmic labor as a taxable economic actor rather than an untaxed substitute for human work.

VI. The Historical Throughline: Technology, Democracy, and Redistribution

Each reform cycle in U.S. history has redefined how innovation’s benefits are shared. The New Deal relied on collective bargaining; the postwar boom used wages and welfare; the neoliberal era turned to asset inflation and debt. Now, in the AI age, redistribution must occur through data governance, automation taxation, and participatory ownership.

In The Value of Everything, economist Mariana Mazzucato delivers a powerful critique of how modern capitalism has come to confuse value creation with value extraction. She argues that the dominant economic narratives—rooted in neoclassical theory and shareholder capitalism—have systematically redefined what counts as “productive” activity, granting disproportionate legitimacy and rewards to sectors that capture existing value rather than generate new wealth for society. A major contribution of the book is its reassertion of the state as a creator of value, not merely a fixer of market failures. Through historical and contemporary examples—from NASA’s role in developing the digital economy to state-funded breakthroughs behind the iPhone—Mazzucato shows that innovation is the outcome of collective, mission-oriented investments, not individual genius or free markets alone.

Similarly, Thomas Piketty’s Capital and Ideology (2020) shows how each technological revolution is also a redistributional revolution — shifting who captures rents from innovation. He argues that inequality is sustained not by economic necessity but by the narratives societies construct to justify it, and that new “proprietarian” ideologies now legitimise data and intellectual property ownership much as past eras sanctified land or capital. In this view, the digital age demands its own egalitarian counter-ideology — one that redefines ownership, participation, and value in the governance of technology itself.

The OECD’s 2023 report on AI and the Labour Market emphasises that redistribution in the AI era must be institutional as much as fiscal, recommending that algorithmic productivity gains be coupled with strong systems of collective bargaining, worker voice, and continuous training to prevent widening inequality. It finds that workplaces with employee representation and structured dialogue experience better working conditions and smoother AI adoption than those without such mechanisms. The IMF (2024) complements this view by showing through macroeconomic model simulations that temporary automation or robot taxes can improve social welfare when worker displacement costs are high—provided that revenues are reinvested in unemployment insurance, reskilling, and wage support. Both institutions converge on a shared principle: technological transitions require fiscal and institutional rebalancing so that automation serves human welfare rather than undermining it.

The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report (2024) warns that without proactive policies, automation will exacerbate inequality faster than any past industrial transition.

Seen through this lens, Sanders’ five proposals form a coherent framework for rebalancing digital capitalism:

The 32-hour week redefines the social distribution of time.

Codetermination democratises the governance of AI-intensive firms.

Profit-sharing and employee ownership redistribute value at source.

The robot tax reclaims automation rents for public investment.

Together, they gesture toward a new social contract in which machines serve society, not the reverse.

VII. The Political Economy of the Future

The challenge ahead is not merely economic but constitutional. When algorithms determine employment, credit, and visibility, the boundaries between technological and political power blur. As Zuboff warned in Surveillance Capitalism (2019), data monopolies now govern through prediction rather than law. The European Union’s AI Act Implementation Report (2024) embodies one response: embedding algorithmic accountability directly into regulation.

The United States, too, is inching toward recognition. The White House Executive Order on AI (2023) invokes “safety, security, and trustworthiness” as governing principles. But the real question is institutional — who decides how AI systems allocate opportunity and risk?

Philosopher Kate Crawford’s Atlas of AI (2021) frames this as a resource problem: AI draws not just on data, but on labour, land, and energy, redistributing environmental and human costs along opaque global chains. Ben Tarnoff’s Internet for the People (2022) adds the civic dimension: democratising digital infrastructure is as vital as regulating it.

Sanders’ speech, then, is less about nostalgia than about constitutional realism. His reforms would transform AI governance from a market-driven process into a democratic one — echoing Roosevelt’s own 1932 declaration that “economic royalists” must not rule a technological republic.

The machine question has returned, but so has the political imagination capable of answering it.

References

Sanders, Bernie. “AI Could Wipe Out the Working Class | Sen. Bernie Sanders.” YouTube video, 42:17. Posted May 20, 2025.

Allen, Robert C. Global Economic History. Oxford University Press. 2011

Aspen Institute. Worker Voice and the Corporate Boardroom, 2021.

Blasi, Joseph, Douglas Kruse, and Richard Freeman. The Citizen’s Share. Yale University Press, 2014.

Congressional Research Service. Worker Representation on Corporate Boards. 2020.

Cooper, Dylan A., Tony Fang, and Vincent Wan. “Employee Ownership and Promotive Voice: The Roles of Psychological Ownership and Perceived Alignment of Interests.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 18023, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), July 2025

Cutler, Jonathan D. Labor’s Time: Shorter Hours. Temple University Press, 2001.

Fitzroy, Felix R. & Nolan, Michael A. “Towards Economic Democracy and Social Justice: Profit Sharing, Co-Determination, and Employee Ownership.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 13238, May 2020.

Forbes. “Maybe It’s Time to Tax the Robots and AI Software.” Forbes, February 22, 2025.

Fulton, Lionel. Codetermination in Germany – A Beginner’s Guide. Mitbestimmungspraxis Nr. 32, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, Düsseldorf, 2020

Homa, Tereza. “Taxation of Digital Economy According to OECD.” In Interaction of Law and Economics: Sustainable Development (ILESD 2023, Brno), Masaryk University, pp. 76–84.

International Labour Office. Working Time and Work-Life Balance Around the World. 2022.

International Monetary Fund. Broadening the Gains from Generative AI: The Role of Fiscal Policies. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/2024/002, Washington DC, 2024.

Lichtenstein, Nelson. Labor’s War at Home. Temple University Press, 2008.

Mazzucato, Mariana. The Value of Everything. Penguin, 2019.

MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future. Building Better Jobs in an Age of Intelligent Machines. 2020.

Noble, David F. Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation. Oxford University Press, 1986.

OECD. Employment Outlook 2023: The Future of Work.

Palladino, Lenore. 21st Century Corporate Governance: New Rules for Worker Representation on Corporate Boards. Working Paper. Roosevelt Institute, September 2019.

Piketty, Thomas. Capital and Ideology. Harvard University Press, 2020.

The Guardian. “Use of AI could create a four-day week for almost one-third of workers.” The Guardian, 20 Nov. 2023.

The Guardian. “Balance Effects of AI with Profits Tax and Green Levy, Says IMF.” The Guardian, June 17, 2024

The New York Times. “Amazon Plans to Replace More Than Half a Million Jobs With Robots.” The New York Times, 21 October 2025

U.S. Department of Labor. Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, [n.d.].

White House. Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence. Washington, D.C., October 30, 2023.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. Profile Books, 2019.